There are many facets to investing in alternative assets such as private equity. The very language of private equity can be mysterious to the uninitiated, such as talk about “J-curves” or “dry powder”. With family offices, private banks and wealthy individuals seen to be increasingly interested in private capital markets as sources of return and diversification, it is important to be clear on terminology. One term that can arise with private equity is the “vintage” of a fund. Caroline Rasmussen, vice president of US-based iCapital Network explains what this term means and why it is important. iCapital Network connects managers of alternative investments with qualified investors. The editors of this news service are pleased to share these views with readers and invite responses. Email tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com

The views of guest contributors are not necessarily shared by this news service.

As in wine production, there is no denying the influence of prevailing conditions on private equity results. A private equity fund’s “vintage” year, the year in which it makes its first investment, effectively starts the clock on the 10-year term of a typical private equity fund. While volatility is not as dramatic as in the public markets, private markets are also subject to cycles in that funds of a certain vintage may benefit from investing into a low-valuation environment and a corresponding ability to ride an economic recovery, while other vintages may have the ill fortune of deploying most of their capital right before a market crash.

Of course, as most would acknowledge, attempting to forecast market conditions over a prolonged period is a futile exercise. Moreover, private equity fund lives are split into an investment period, typically five years, and a subsequent harvesting period, when the exit environment becomes more relevant. The fact that PE fund investments are not made in one lump sum but rather the committed capital is deployed over several years gives managers a fair amount of flexibility, and makes it impossible to predict the predominant investment environment for a given fund. One might think for example that distressed funds that completed their fundraising in 2007 would have fared relatively well, with ample time to take advantage of the post-crisis dislocation. Certain skilled managers indeed did perform exceptionally well with their 2007 funds. But the median net IRR for 2007 vintage distressed funds was just 5.3 per cent according to Burgiss data, compared to almost 14 per cent for 2008 vintage funds. Many private funds that held their final close in 2007 had deployed significant capital in 2006 during their fundraising process and thus ended up with numerous impaired investments following the 2008 financial crisis.

Interestingly, investors who waited for markets to fall before committing capital to distressed funds would have given up about 350 basis points of return compared to those who committed before the crisis and found themselves with 2008 vintage exposure in funds that had kept most of their powder dry and made few investments prior to the downturn. Thus, for a sharpshooting, vintage timing approach to be successful, one would have to know in advance not just which multi-year period will present the most favorable investment environment for a given strategy, but that the selected manager will in fact deploy the majority of their capital during that concentrated period. In other words, trying to cherry pick vintage years for private equity would require exceptional market foresight and macro timing.

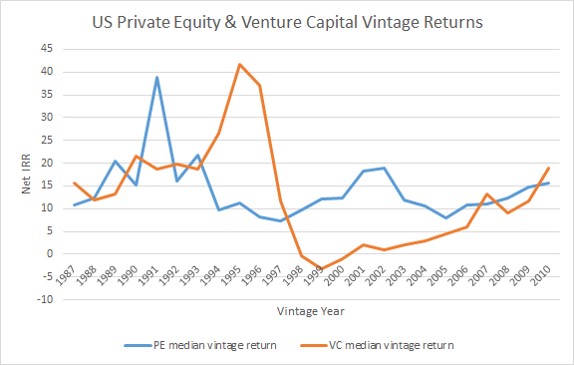

To provide another example, one might reasonably assume that buyout and venture capital funds would tend to perform similarly across cycles. In fact, as shown in Figure 1, buyout and venture capital returns have exhibited meaningful counter-cyclicality, despite both being equity oriented. Timing the markets in the context of performing fundamental analysis on individual, liquid stocks is difficult and speculative enough, but given the nature of private equity fund investing, a vintage selection approach that attempts to predict both market conditions and the performance of specific strategies far into the future has a slim chance of consistent success. This underscores the basic need when constructing private equity allocations not only for diversification by manager but diversification by strategy and vintage.

Figure 1

Cambridge Associates data as of 9/30/2016

What most effective investors in the PE asset class have found is that the best strategy is to focus one’s efforts on singling out experienced managers who can take advantage of favorable investment conditions if they do occur , but who also have the networks, discipline and industry expertise to avoid overpaying in frothy markets, develop and execute clear value creation plans at portfolio companies, and identify the most accretive selling opportunities in any given market environment. After all, the central value proposition of private equity is to maximize value via improved operations no matter what the market context, as well as to exercise selectivity and discipline in both capital deployment and portfolio dispositions - skills that are either simply unavailable to the individual investor in public equities, or are very difficult to apply, as demonstrated by basic behavioral finance.

The importance of peer comparison

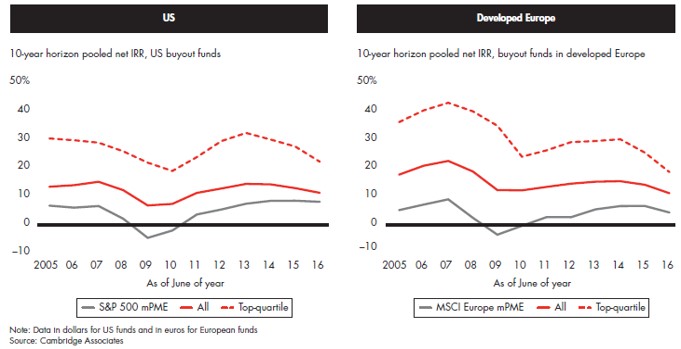

A superior winery will tend to produce better product on average across vintages compared to a mediocre vintner. Similarly, experienced, talented private equity managers demonstrate the ability to consistently add value in both bull and bear markets. Separating these superior managers from the pack requires comparing returns with those of other funds of comparable size and strategy in the same vintage year. It also requires parsing out how much of the return was generated by multiple expansion , versus from revenue and EBITDA growth in their underlying portfolio companies . As shown in Figure 2, the spread between private equity beta and the asset class’ top performing funds can exceed 1,000 basis points.

Figure 2

Bain 2017 Global Private Equity Report

In sum, manager selection in private equity is ultimately far more important than vintage selection, and has the added virtue of actually being a feasible exercise. There has been much press recently regarding stretched valuations in both public and private markets. Investors concerned about this but who still want to retain equity exposure should simply concentrate on identifying, on both the public and private side, managers who are fundamentally deep value investors with a history of not overpaying for assets. Jumping in and out of the asset class based on one’s expectations of market conditions creates the very real risk of over-allocating to what turns out to be a weak vintage, and missing out on what turns out to be a strong vintage.

A steady allocation pace across vintages adds critical diversification both within private equity allocations and in the context of the broader portfolio, helping to mitigate risk in a similar fashion as dollar cost averaging. Diversification is your friend in private markets as much as it is in public markets, with successful PE investors tending to commit capital not just to top quartile managers but across vintage years as well. Give yourself every advantage by consistently investing with general partners who can create and protect value in a variety of circumstances.